A Partial List of Unarmed African-Americans who were Killed By Police or Who Died in Police Custody During My Sabbatical from Massachusetts College of Art and Design, 2014-2015, 2016

There are three deaths. The first is when the body ceases to function.

The second is when the body is consigned to the grave. The third is that

moment, sometime in the future, when your name is spoken for the last time.

—David Eagleman, Sum: Forty Tales from the Afterlives

I went on sabbatical from teaching last year. It was one of those things that I, a kid of working class parents, could never have imagined when I was younger. My institution was enabling me to take time off of work to concentrate on my artistic development: to focus on my studio the way that I have been focusing on my students for the past 10 years. This time was hard-won, precious; I was looking forward to it opening up for me. I had a lot of ideas that had filled my sketchbooks over the years. Also, I had bookcases of texts I could not wait to devour. It had been so long since I had read anything for pleasure, I was so looking forward to curling up with all the tomes I had purchased that work had not allowed me to open. Also, to be perfectly honest, I was looking forward to getting some rest. I purchased supplies and cleared out my studio for new work. I cleaned up my email and finished up school business. I got to a clutter-free place. I thought about what was possible.

Then Michael Brown happened.

While news channels kept showing his body lying in the street for hours, we found out about John H. Crawford, III.

And then Ezell Ford. And Dante Parker. And Kajieme Powell. And more. And many, many more. Some captured in grainy videos replayed on television and computer screens.

In the studio, I could not stop thinking about this march of death. I painted almost every day, and every day this parade of killing was on my television and radio and social media feed. Some of the dead became Twitter hashtags. Some did not, but they were no less dead. Why were some people more important than others? Did people think that some victims were more worthy than others of not being shot to death, or tasered to death, or run over, or beaten to death by the state?

I was on sabbatical, so I had time. Time to create turned into time to think, and I couldn’t think about anything other than death. I didn’t read any books. I painted.

It’s summer (July), and I’m at dinner with a friend. We are in a bistro with televisions all over the restaurant and bar area. The sound is turned down, but the images light the entire place. The video of Officer Daniel Pantaleo choking Eric Garner to death plays over and over and over, interrupted by silent talking heads. I wonder, why are they playing this man’s murder on a loop? People eat, drink, laugh, walk about. No one seems to notice that a man is being choked to death on television. Then I start to think that maybe they do see it and that it doesn’t bother them. This is the first time I witness this, a black person being killed on television. It will not be the last time. Not by any measure.

Over the course of my sabbatical, I see black people shot to death on television over and over again. Newscasters and pundits issue verbal warnings that the video they are about to show might upset “sensitive viewers.” I try to imagine a viewer who would not be upset about seeing someone like Walter Scott shot to death (or by the fact that his killer, Officer Michael Slager, planted evidence on his corpse).

Or Tamir Rice shot to death. I wonder why they don’t tell the “insensitive viewers” to hook up their DVRs. When I am in the studio, the images filled my head. I jump when cars backfire.

People ask me how my sabbatical is going. They say, “I hope you are taking advantage of this time.” They tell me how lucky I am. They ask, “What’s going on in the studio?” I wonder if they watch the news at all. I wonder if they know about what is happening. I wonder how they feel about these images of black people being killed. I post about this stuff on social media, and it is ignored, for the most

part. Ferguson explodes. Social media does not believe in tears.

In August of 2015, two reporters are shot to death on live television. Alison Parker and Adam Ward are killed by Vester Lee Flanagan II, who uploaded a video of the killing to social media. Immediately, the television station, Facebook, and other social media erupt with requests for people not to view or share the video. To maintain the dignity of the victims, people beg the public not to watch the video. It would be a terrible thing to give the killer satisfaction by watching his murder of the reporters.

I start to wonder why black people are allowed to be killed on television. Why we are allowed to be transformed from subjects to objects and left to lie in streets for hours? Why is it acceptable to show the end of a black life on television?

I start to make work about the historical impulse to turn violence against black people into part of our domestic structures. People continue to ask me what I am doing on sabbatical. I think of Neruda and I wish I knew Spanish. (“Come and see the blood in the streets... ”) I decide to make a work about all the people killed by police while I was on sabbatical. I dismiss the idea as too agitprop. I talk to my mentors. One of them tells me, “Make the work. Just don’t trivialize.” I work with a friend and learn how to make photographs. It is harder than I imagined. I finish this work, Family Pictures. I show it to a few people. I finish my sabbatical. I’ve read few books. I feel surrounded by ghosts.

I paint everything I think. I don’t trivialize. I realize a new body of paintings. My studio is full of murderers, victims, liars, and accusers.

I return to work in September. In December, I am hassled and detained by the police. I write about the experience. Many people want me to come and talk to groups to “raise awareness.” I decline. They seem to be unaware that I would not like to relive a traumatic experience in public. People want me to talk about #BlackLivesMatter. The college intervenes and offers to handle calls from the press for me. I am deeply grateful, because this allows me to concentrate on my job and my students. CNN calls the college and wants to know if I will talk to Don Lemon. I tell the school that I will talk to anyone at CNN except Don Lemon. I get hate mail.

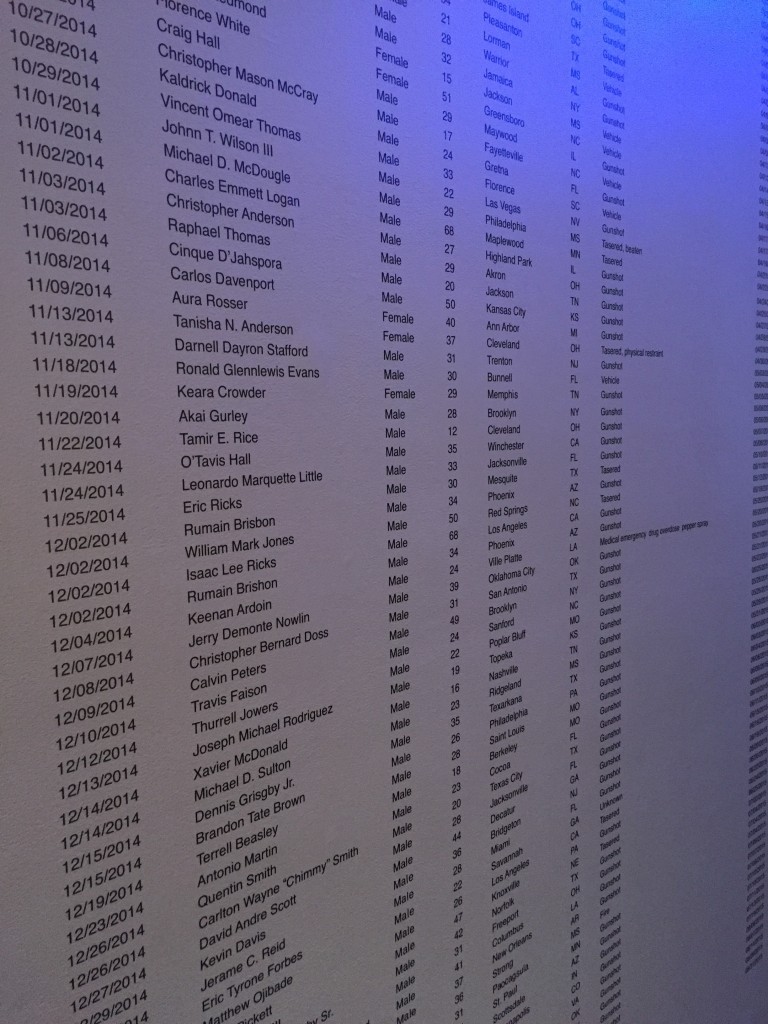

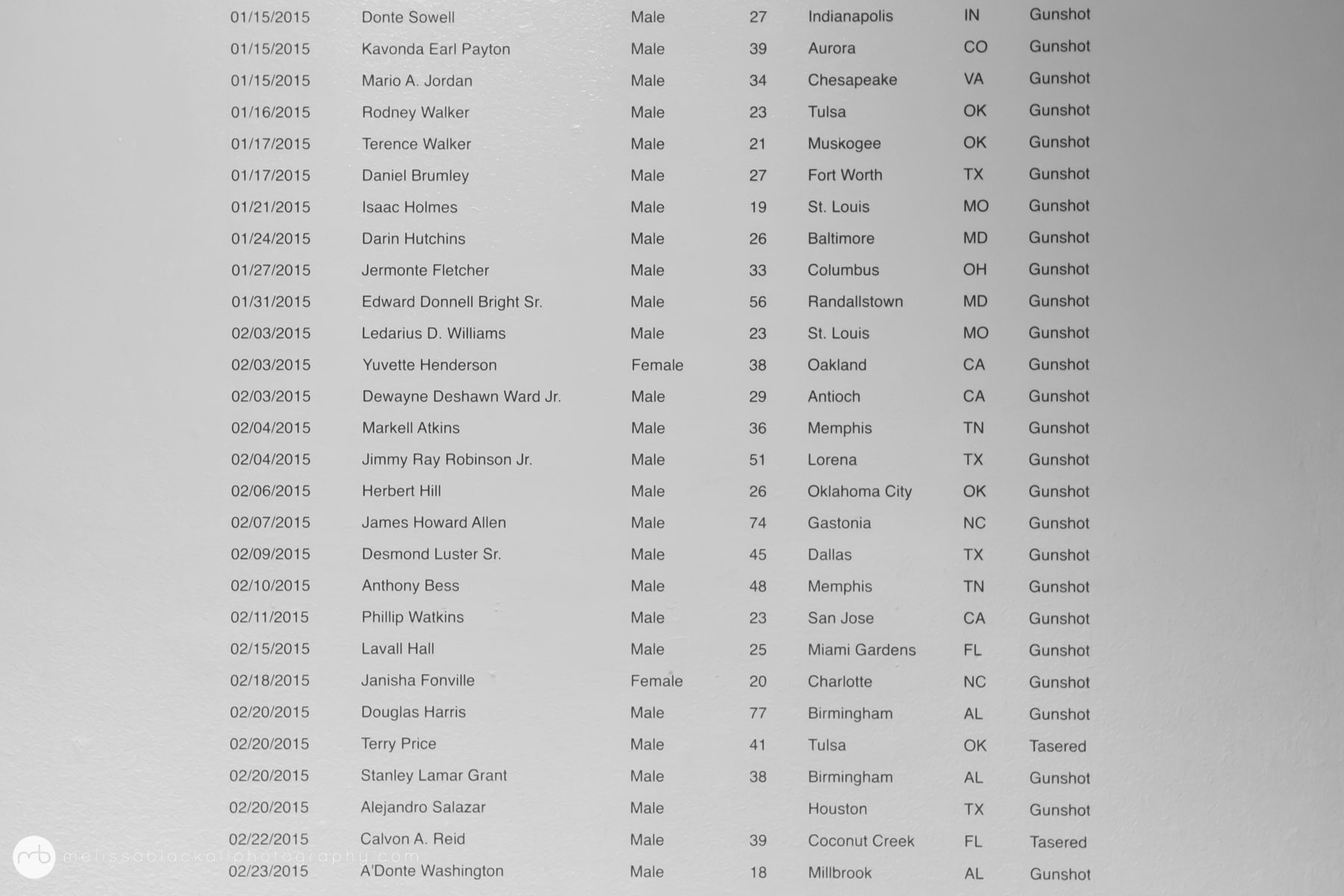

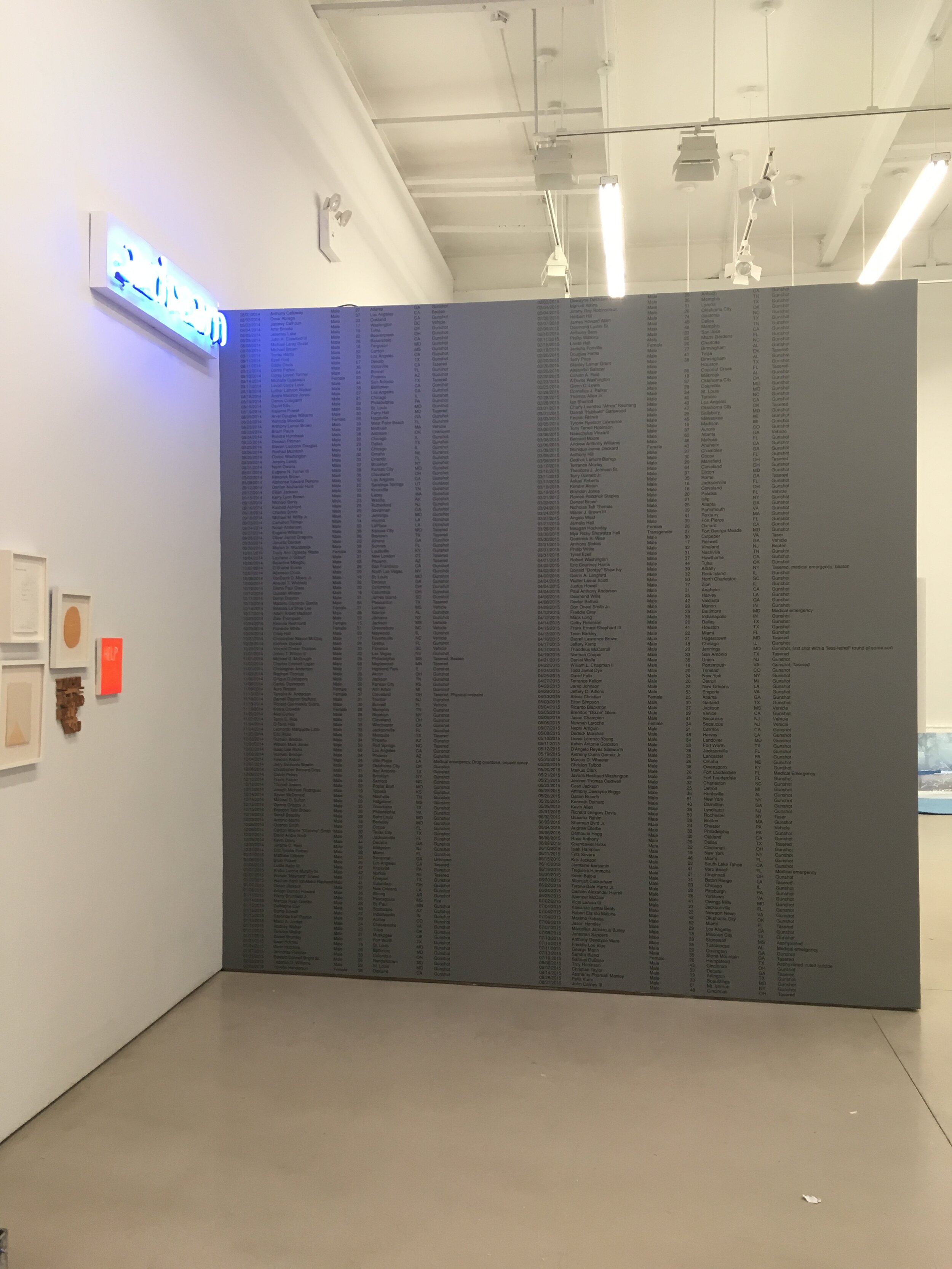

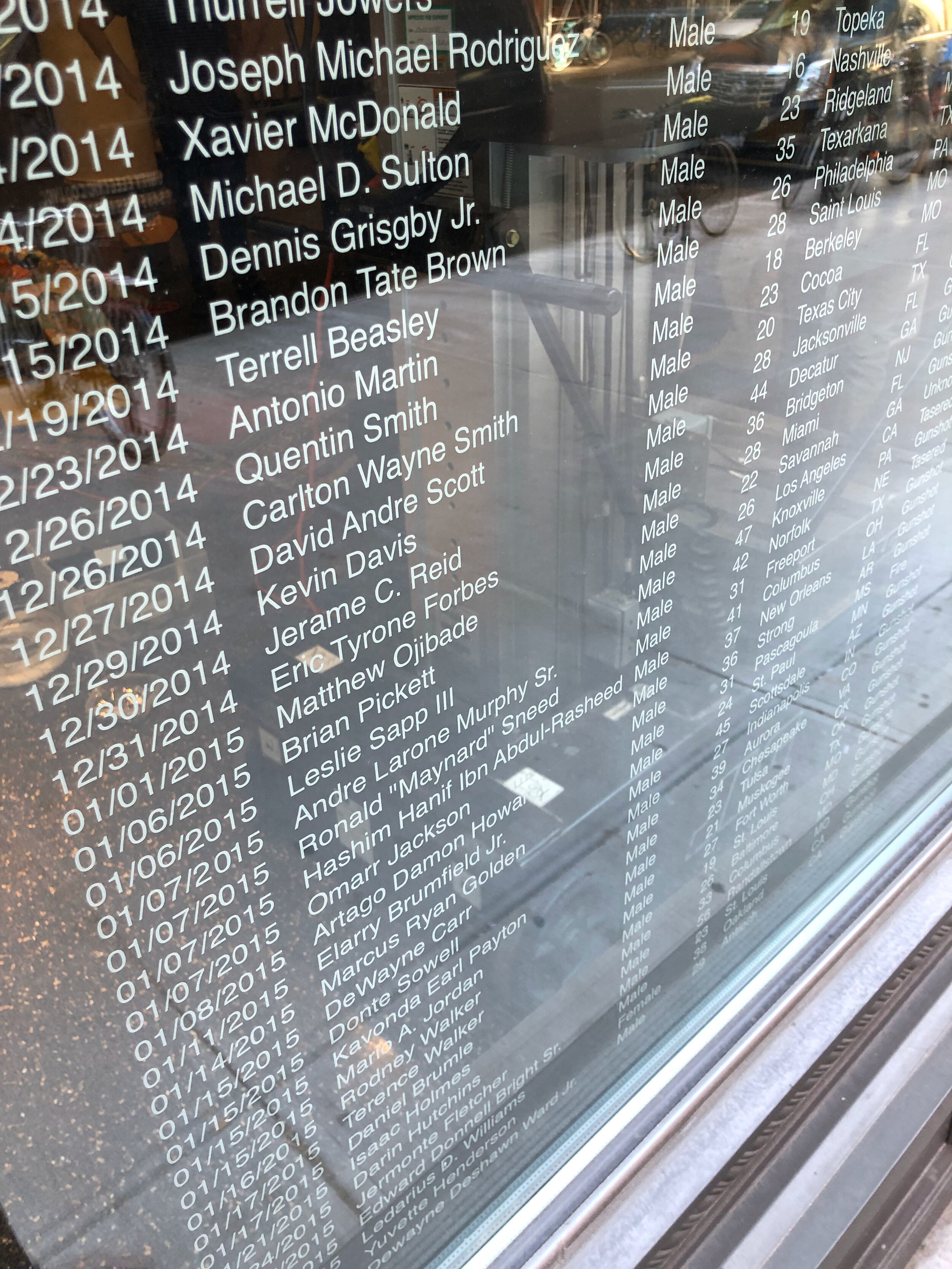

Lisa Tung, the exhibitions director at the college, asks me what work I want to put in the biennial faculty show. I decide to make the piece I thought was agitprop. I call Carmine, my neon fabricator. I want him to make a sign that mimics police light and spells out what is lost. I research police killings of unarmed civilians. I find no central list. I find no definitive list. I find no government statistics. I rely on activist sources. I rely on the Guardian. I make the piece. It is installed in the faculty show. It is a timeline. Its information: date, name, gender, city, state, method of killing. I title it “A Partial List of Unarmed African-Americans who were Killed by Police or who Died in Police Custody During my Sabbatical from Massachusetts College of Art and Design, 2014-2015.”

Steve Locke, “A Partial List of Unarmed African-Americans who were Killed by Police or who Died in Police Custody During my Sabbatical from Massachusetts College of Art and Design, 2014-2015” (2016), paint on wall with vinyl text, neon, dimensions variable

There are 262 names.

People tell me that they look at the wall and measure time. They lift up the people in their thoughts. Someone asks me if I am influenced by Maya Lin. I answer that we all are influenced by Maya Lin.

Someone will say their names, and they will be alive a little longer.